“That’s the way it crumbles…cookie-wise.” – Jack Lemmon as C.C. Baxter in The Apartment The Film and Performance: When The Apartment was first released into theaters, it effectively held up … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: The Apartment (1960)

“That’s the way it crumbles…cookie-wise.” – Jack Lemmon as C.C. Baxter in The Apartment The Film and Performance: When The Apartment was first released into theaters, it effectively held up … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: The Apartment (1960)

“The most important thing in life is to learn how to give out love and to let it come in.” – Jack Lemmon as Morrie Schwartz in Tuesdays with Morrie … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: Tuesdays with Morrie (1999)

*This film can be watched in its entirety on YouTube

The Film and Performance:

In 1925, teacher John Scopes was accused of violating a Tennessee law that made it unlawful to educate students about Darwin’s theory of evolution, especially human evolution, in any state-funded school. This became known as the “Scopes Monkey Trial.” During the Trial, the defense led by Clarence Darrow argued that the trial wasn’t merely about creationism versus evolution, but about free thought and having the right to express that thought. In contrast was three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, who was adamant that the word of God as expressed in the Bible was the final word on all aspects of life. The trial ultimately concluded with Scopes being found guilty, but rather than incarcerate him, he was charged with the feeble fine of $100 dollars (equivalent to $1300 in 2015). Despite the guilty verdict, Darrow proclaimed the trial a victory because it brought about national attention to a law that was unconstitutional. In that regard, he was correct. Advocates soon fought for the sake of science, ultimately exhausting the anti-evolution movement by the mid 1930s.

Inherit the Wind is a dramatization of the “Scopes Monkey Trial.” It debuted as a play, premiering in 1955. Despite the play’s numerous inaccurate representations of the real-life trial, the play was a tremendous success with many at the time linking similarities to the “Scopes Monkey Trial” to the then McCarthyism era. It became a film in 1960 starring Spencer Tracy and Fredrick March. The film was considered one of the best films of the year and received four Oscar nominations, including one for Best Picture. Since the 1960 film, there have been various TV adaptions. The 1999 Jack Lemmon and George C. Scott version is one of these television adaptions.

Inherit the Wind may be directly about the “Scopes Monkey Trial” but it functions more as symbolism for conformity versus individualism. The action within the play or films showcase a community that demands a single way of thinking and vilifies anyone who does not adhere to their ideology. The teaching of evolution contradicts what has been established as the normative behavior of the community and they react harshly to silence that outside opinion. In that regard, Inherit the Wind has remarkable relevancy to today’s society where pressure to conform continues to be a major issue.

The problem with the 1999 television version is that it offers nothing new to audiences other than being another interpretation of the original play/film. Therefore it becomes painfully evident that the production of this film put the majority of its focus on the casting of Jack Lemmon as Henry Drummond, the crusader for evolution and George. C. Scott as Matthew Harrison Brady, the staunch defender of the Bible. Outside of these two lead actors, the film is stale and almost abhorrent to view.

What especially destroys what could have been a stellar adaption is the inferior, and downright awful supporting cast of this film. There is a blatant mixture of under and over acting in this film to the point that it even disrupts the pacing and tone of the film. Scenes that had the potential to be impactful nearly become laughable. Worst of the supporting cast is Tom Everett Scott as the accused, named Bertram Cates in this adaption. Everett Scott showed absolutely zero range and his acting was so deadpan that the actor’s disinterest in the filming of this film was abundantly clear. It is also painfully obvious that the director of this film was aware of this bad acting from Everett Scott and desperately tried to limit his on-screen presence. Considering the film’s script is almost verbatim from its source material, it reinforces the long-standing claim that the success to any play (or its adaptions) is having a strong ensemble cast to support each other. Even so much as one bad actor can ruin an entire show and diminish the extraordinary talent that has managed to occur. With the 1999 version of Inherit the Wind, the entire cast outside of Jack Lemmon, George C. Scott, Beau Bridges, and Piper Laurie are downright awful and drag this movie down from being enlightening to forgettable.

The film’s saving grace is Jack Lemmon and George C. Scott, who both were magnificent in their dueling roles. Having recently faced off against each other in the television remake of 12 Angry Men in 1997, it is evident producers wanted to recreate that dense drama in this film and that was a wise decision. Yet Lemmon and Scott were sure not to merely copy their 12 Angry Men rivalry into this film. Instead, they crafted their performances as two individuals who deeply respect each other but find themselves on opposite sides of an issue they are passionate about. Instead of framing their performances as two persons determined to win, Lemmon and Scott craft their characters’ interactions as if they are playing an elaborate game of chess, each of them hoping to checkmate the other in defeat. This mutual animosity towards each other allowed for both characters to be liked and respected despite their clear differences.

Yet it is their courtroom scenes where they both excel, especially Lemmon. Both actors brilliantly captured the tension and frustration of trying to convey their ideals and thoughts in these court scenes. Of the two, Lemmon had the more arduous performance as someone who has been limited almost the point of submission, but still fights for what is right. Additionally, Jack Lemmon had to truly represent himself as an outsider in a conformist community in order to adequately sell the performance and he does, establishing the character as methodical, careful, but knowing when strike with his words. For Lemmon, this was a fantastic performance. The only flaw comes in that it is diminished due to a very poor supporting cast that distracts from his overall performance.

Inherit the Wind is one of two films (the other being Tuesdays With Morrie) Jack Lemmon starred in 1999, the last year he acted in film before his death in June 27, 2001. For this performance, Jack Lemmon won his final Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actor in a Miniseries or Motion Picture Made for TV. To view Jack Lemmon’s acceptance speech, click HERE. He was also nominated for a Primetime Emmy as Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or Movie, but didn’t win.

The Film:

2.5/5

The Performance:

5/5

“I want that girl in a Cole Porter song. I want to see Lena Horne at the Cotton Club…hear Billie Holiday sing fine and mellow…walk in that kind of rain … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: Save the Tiger (1973)

The Miniseries and Performance: In 1913 Georgia, Mary Phagan, a young, 13-year-old factory worker was murdered and her body was found in the cellar of the factory she worked in. … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: The Murder of Mary Phagan (1988)

*This play/miniseries can be watched in its entirety for free HERE

The Movie and Performance:

Between the years of 1941-42 playwright Eugene O’Neill penned the four act play entitled Long Day’s Journey into Night. O’Neill was a prolific playwright, whose work was among the first to portray the underbelly of society. His plays were stunningly dramatic and often presented an image of individuals who thrive off pessimism and the devaluing of others. Due to this unique writing vantage, O’Neill was recognized for his work and received many accolades as a result. During his life, O’Neill was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama three times for Beyond the Horizon (1920), Annie Christie (1922), and Strange Interlude (1928). O’Neill would ultimately be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936. Despite these tremendous successes, Long Day’s Journey into Night is still considered to be O’Neill’s greatest play, if not one of the greatest plays of all time. Ironically, O’Neill never lived to see the play performed. The play was not published until 1956, three years after his untimely death. O’Neill had stipulated that Long Day’s Journey into Night, which he considered to be autobiographical, not to be published until 25 years after his death. His widow, actress Carlotta Monterey, decided to have the play published hastily regardless of O’Neill’s wishes. She was able to achieve this by transferring the rights of the play to Yale University and having all proceeds from the play benefiting the Eugene O’Neill Collection, such as the establishment of drama scholarships for the school. As a result, Long Day’s Journey into Night, for the first time, was able to be produced as a Broadway play. It was an instant success and even succeeded in winning O’Neill posthumously the Tony for Best Play in 1957, but also the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

O’Neill considered Long Day’s Journey into Night to be a very personal, autobiographical narrative that revealed much about his life and family. The correlations are stunning when contrasting them with his own life. The play’s themes of addiction, lives that once were, aspirations lost, and the concept of truth, were all aspects of O’Neill’s own upbringing that dramatically affected him. His father, James O’Neill, was once a successful actor who lost his career when accused of “selling out” and later became an alcoholic. His mother, Mary, was deeply religious, had attended a Catholic school, but was tragically addicted to morphine after the birth of her third son, Eugene. Addiction was prevalent in his family with O’Neill’s brother, Jamie, ultimately drinking himself to death. O’Neill’s own sons suffered from addiction. Eugene O’Neill Jr. was an alcoholic who committed suicide in 1950 and Shane O’Neill was a heroin addict who would also commit suicide in 1977. Eugene O’Neill further suffered from tuberculosis, to which he was sent to a sanatorium to recover, which would be the basis of conflict within the play. When detailing the personal life of O’Neill, it becomes immediately evident as to why Long Day’s Journey into Night is considered to be his most profound work. It is because the play was a cathartic confession about his upbringing, presenting a bleak and hopeless image of persons who have mentally given up their aspirations and have settled for a life of despair and addiction.

It should be noted that Long Day’s Journey into Night is not a play meant for entertainment. It is an uncomfortable representation of true-life, giving the audience a vantage of a family’s personal conflict with each other and life. The play occurs in the span of one day and centers around the Tyrone family, who live in a cottage in Connecticut. The foundation of the story centers around Edmund, who has been diagnosed with tuberculosis and will be sent to a sanatorium in the next day to recover. This information is being deliberately kept from the family matron, Mary, who is a morphine addict and recently back from the hospital. However, the family patriarch is a self-absorbed man who hides himself from the truth, especially with his alcoholism. The play functions more off its themes than plot and characterization. Interaction is how the play thrives and progresses the narrative forward. The Tyrone family thrives off memories of the past, yet those memories are skewed, challenging the concept of truth. As Mary Tyrone blatantly states, which is a prevalent theme in the play, “I only want to remember the parts of the past that make me happy.” Ironically that statement, when put in use by the various characters, conveys profound sadness of individuals reflecting on lives they could have had and what they have settled for. This burden of truth is too impactful for such characters, who then utilize addictive substances to escape reality. The issue is that the stand-still nature of their lives leave them with no substantial goals or life aspirations. They merely exist, and as a result, they suffer daily due to it.

Ironically, in contrast to the characters’ avoidance of it, the play is brutally honest. Long Day’s Journey into Night doesn’t offer redemption or chances of hope because that is not the reality presented with the Tyrone family. This family consists of persons already lost and the events that occur within this single day is part of a never-ending cycle of despair, depression, and probably death.

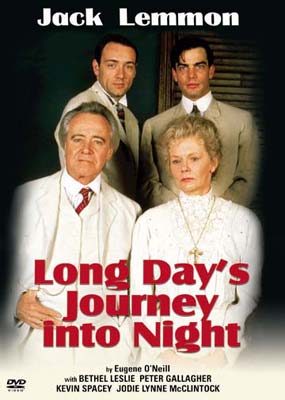

This 1987 television “miniseries” version of the play shouldn’t be considered a miniseries at all. The reasoning behind this is because this adaption of Long Day’s Journey into Night was a mere taping of their highly successful 1986 Broadway revival of the play. This “television adaption” consisted of a single, simple set where all characters interact within. There is no music and there are minimal scene transitions. The only variation is the multiple camera angles that give the viewer of the play the best possible vantage of the action occurring upon the stage. This was filmed precisely how it was intended to be presented to the viewer by Eugene O’Neill. It is devoid of anything that would liven its content or any Hollywoodization. Furthermore, this revival was a successful Broadway production that was staged at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York. This revival was recognized at the 40th Tony Awards (1986) with nominations in the play categories for Lead Actor (Jack Lemmon), Featured Actress (Bethel Leslie), Featured Actor (Peter Gallagher), and Direction (Jonathan Miller).

The 1986 revival is stunningly brilliant. In order for the play to be functional and impactful, the language of the play must be delivered in a specific manner. The cast does not falter even slightly. Jack Lemmon, especially, is incredible in his acting by delivering his lines with disdain and a contemptuous demeanor. Lemmon’s acting conveys James Tyrone as an individual who has blinded himself to his past, is self-absorbed, and compensates his failures by asserting himself as the ultimate authority figure. Lemmon also perfectly captured the denial of alcoholism throughout the play, emphasizing aggression and irritation when being called out on it, yet seeking the first opportunity possible to begin drinking and continue that process. It’s not until the play’s fourth act when James Tyrone is drunk that Jack Lemmon was able to infuse incredible vulnerability and tragedy into the character when he laments about his former stage career and how he lost it when he became typecasted. Yet despite that, during Lemmon’s near 50-minute monologue, he was still able to interject instances of superiority and resistance to the truth. Lemmon conveyed the character as someone who desires to be pitied, yet becomes infuriated when others do precisely that. This was such a different performance for Jack Lemmon, one that deviated from anything he had achieved before in his career. In short, Jack Lemmon is brilliant in the lead role of Long Day’s Journey into Night.

However, the real scene-stealer from the play was Bethel Leslie as Mary Tyrone. Her performance as the fragile, morphine-addicted matriarch is a presence that demands attention. She crafted the character as someone who is so ashamed of her current circumstance, continually reflecting on a past that could have been. She laments about how she could have been a nun or concert pianist, but chose marriage instead, leading her into a life of misery and social isolation. Her drug usage is her crutch to escape that circumstance and sadly remind herself, when she’s alone, of instances of the past she can cherish. Ironically, the drugs are also a truth serum for her when she is in the company of her family, causing her to directly call out their failures and their hypocritical nature. Bethel Leslie was stunning that regard, having the behavioral demeanor of Mary Tyrone fluctuate from being loving to infuriated within a matter of seconds. Her line delivery in such scenes are incredible by how she was able to pour paragraphs of scathing commentary to all those around her while her facial expressions were that of pain and torment. The greatest achievement of Bethel Leslie was her being the figure of suffering within the play. She gave the character sympathy in her portrayal, but also was sure to offer enough conflict in her personality too, conveying to audiences she’s no better than the rest of the characters surrounding her. In her vast career, Bethel Leslie is primarily remembered for this performance, and it is completely understandable as to why.

Since this production was filmed and aired on television, it was submitted and eligible for both Emmy and Golden Globe nominations. Jack Lemmon was nominated in the Lead Actor in a Miniseries category at the 1987 Golden Globes for his portrayal as James Tyrone. He unfortunately didn’t win.

The Play/Movie:

5/5

The Performance:

5/5

Go Back to Jack Lemmon Homepage

The Movie and Performance: Clearly riding off the nostalgia of the Grumpy Old Men franchise, it was evident that producers thought they had a renewed vehicle for Jack Lemmon and … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: Out to Sea (1997)

The Movie and Performance: Oftentimes when a sequel is made for a film, it is produced in an effort to bank off of the success of the previous film. With … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: Grumpier Old Men (1995)

The Movie and Performance: By 1993, It had been twelve years since Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau starred in a movie together as a comedy duo. Their previous work together … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: Grumpy Old Men (1993)

The Film and Performance: *Warning: review contains film spoilers The 1973 Chilean coup d’état was a brutal and infamous part of the Cold War. The culmination of events occurred when … Continue reading Jack Lemmon: Missing (1982)